Before there were assembly lines, before electric starters, before seat belts - there were just horses, wooden wheels, and a few bolts holding together something called a ‘horseless carriage.’ The first real car parts weren’t designed for performance or comfort. They were designed to keep the thing from falling apart. And that’s where the story really begins.

The Birth of the Car Part

In 1886, Karl Benz built the Motorwagen - widely accepted as the first true automobile. It had three wheels, a single-cylinder four-stroke engine, and a wooden frame. The parts? Almost all of them were borrowed from other industries. The engine came from stationary engine makers. The tires were solid rubber, like those on wagons. The steering mechanism? Adapted from bicycle handlebars. There was no such thing as a ‘car part’ back then - just parts that happened to be used in cars.

By 1900, a few dozen manufacturers were building cars in Europe and the U.S. Each one made their own parts. A Ford part wouldn’t fit a Cadillac. That meant if your carburetor broke, you either fixed it yourself or waited weeks for a custom replacement. No standardization. No catalogs. No auto parts stores. You were on your own.

The Rise of Interchangeability

Everything changed when Henry Ford introduced the Model T in 1908. He didn’t just want to build cars - he wanted to build them fast, cheap, and in huge numbers. That required something revolutionary: interchangeable parts.

Before Ford, every gear, bolt, and spring was hand-fitted. One mechanic’s carburetor might not work on another’s car, even if they were the same model. Ford’s factories used precision machinery to produce parts within tolerances so tight that any part could go into any car. This wasn’t just about efficiency - it was about survival. If you broke a part on the road, you could buy a replacement from any dealer and install it without modification.

By 1915, Ford was producing over half a million Model Ts a year. And suddenly, the idea of ‘car parts’ as a category took root. People started buying spare parts just in case. Repair shops opened. Mechanics became professionals. The aftermarket was born.

From Brass to Plastic: Materials That Changed Everything

Early cars were made of steel, brass, leather, and wood. Brass was everywhere - radiators, headlights, door handles. It looked elegant, but it tarnished quickly and was expensive. By the 1920s, manufacturers started switching to painted steel. It was cheaper, stronger, and didn’t need polishing.

Then came plastics. In the 1950s, companies like General Motors began using Bakelite for knobs and dashboards. By the 1970s, polypropylene and ABS plastic were replacing metal in bumpers, air ducts, and interior trim. Why? Weight. Cost. Safety. A plastic bumper could absorb impact without crumpling the frame. A plastic dashboard wouldn’t shatter on impact like glass or metal.

Today, over 50% of a modern car’s weight is made of plastic and composite materials. That’s not just convenience - it’s physics. Lighter cars use less fuel, emit less CO₂, and handle better. The shift from brass to plastic didn’t just change how cars looked - it changed how they moved, how long they lasted, and how they were repaired.

The Electronics Revolution

For most of the 20th century, car parts were mechanical. A throttle cable pulled open a valve. A distributor sent sparks to the right cylinder at the right time. You could fix most things with a wrench and some patience.

Then, in the 1980s, computers showed up. The first electronic fuel injection systems were clunky, unreliable, and expensive. But they worked better than carburetors in cold weather. By the 1990s, every new car had an Engine Control Unit (ECU) - a small computer that managed fuel, timing, emissions. Suddenly, a ‘car part’ wasn’t just a physical object. It was a sensor, a circuit board, a software code.

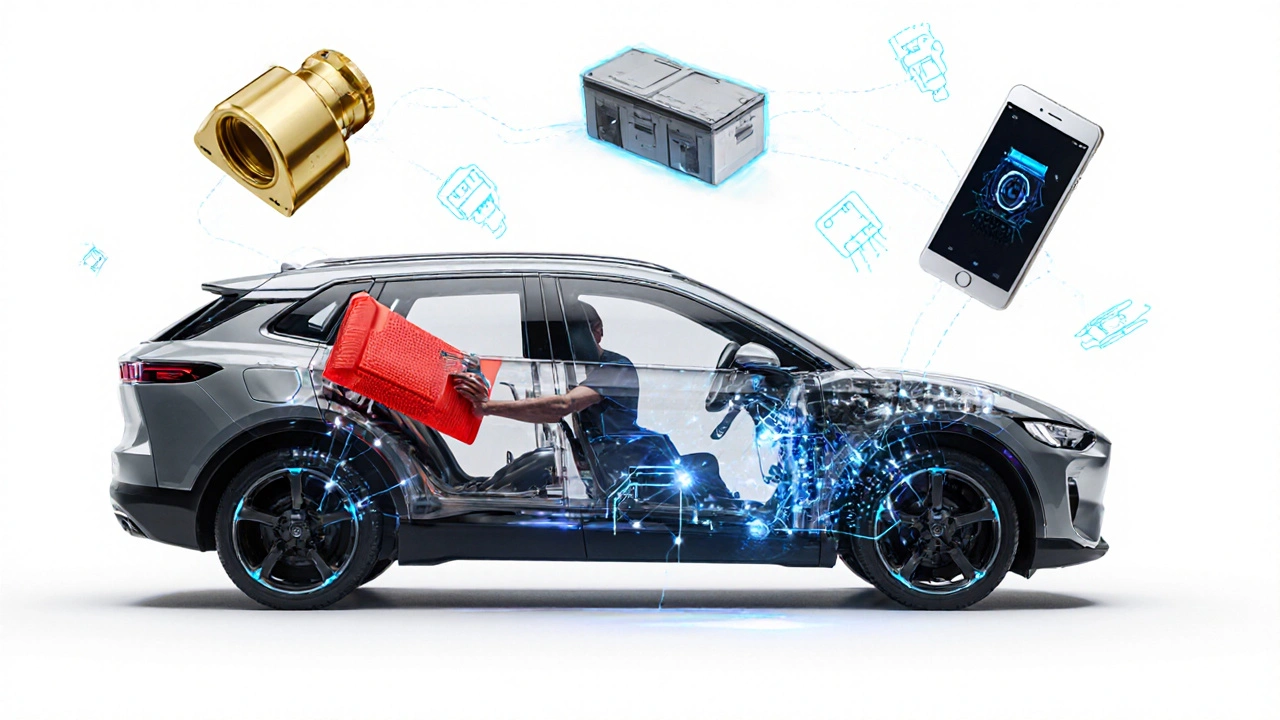

Today’s cars have over 100 electronic control units. The airbag system talks to the brake system, which talks to the stability control, which talks to the GPS. If your oxygen sensor fails, the ECU doesn’t just turn on a warning light - it adjusts the entire engine’s behavior. You can’t fix that with a screwdriver. You need a scanner, a database, and training.

This shift turned mechanics into technicians. It turned spare parts into complex modules. And it made repairs more expensive - but also more precise. A modern car doesn’t just run. It talks.

The Aftermarket Explosion

As cars got more complicated, so did the parts that fix them. The aftermarket - companies that make replacement parts outside the original manufacturer - exploded. In the 1960s, you could buy a replacement headlight from a local hardware store. Now, you’re choosing between OEM (original equipment manufacturer), aftermarket, and used parts from salvage yards.

OEM parts are made by the same company that built your car. They’re expensive, but they match the original specs exactly. Aftermarket parts are made by third parties. Some are just as good. Some are junk. Then there’s the used market. A 2012 Honda Civic might have a perfectly good alternator in a junkyard in Ohio, shipped to a garage in Texas for $40.

Online retailers like RockAuto and Amazon have made it easier than ever to find parts. You can search by VIN number and get the exact part for your car - down to the color of the plastic clip. But with that convenience comes confusion. How do you know if that $15 brake pad is safe? That’s where reputation, reviews, and certifications like CAPA (Certified Automotive Parts Association) matter.

What’s Next? Electric, Modular, and Self-Repairing

The next big shift isn’t about materials or electronics - it’s about purpose. Electric vehicles don’t need spark plugs, oil filters, or exhaust systems. That means hundreds of traditional car parts are disappearing. A Tesla has fewer than 20 moving parts in its drivetrain. A gas-powered car has over 2,000.

And it’s not just about fewer parts. It’s about smarter ones. Companies are experimenting with modular designs - where entire subsystems (like the battery pack or motor) can be swapped out like a phone battery. Some prototypes even include self-diagnosing sensors that alert you before a part fails.

And then there’s 3D printing. In 2023, a mechanic in Oregon printed a replacement fuel line bracket for a 1998 Toyota Camry that hadn’t been made in 15 years. He used a CAD file from a hobbyist forum, a $500 desktop printer, and a spool of nylon. It worked. For the first time, you don’t need a factory to make a car part - you just need a design and a printer.

Why This History Matters Today

When you replace a headlight or a thermostat, you’re not just fixing a car. You’re participating in a 140-year-old story of innovation, adaptation, and survival. The parts you buy today carry the legacy of Benz’s brass radiator, Ford’s precision jigs, and Tesla’s battery modules.

Understanding that history helps you make smarter choices. It tells you why some parts cost more - not because they’re branded, but because they’re engineered to last. It shows you why some repairs are simple and others require a computer. And it reminds you that the car you drive today is the result of millions of tiny improvements, failures, and breakthroughs.

Next time you hear a rattle under your hood, don’t just reach for a wrench. Think about the people who made that part possible - the machinists, the chemists, the software engineers, the junkyard workers who saved a piece of history so you could keep driving.

What was the first car part ever made specifically for automobiles?

There wasn’t one single ‘first’ car part made just for cars. Early automotive parts were adapted from other machines. The first true automobile, Karl Benz’s Motorwagen (1886), used a single-cylinder engine originally designed for stationary use, bicycle-style steering, and solid rubber tires from horse wagons. The first parts made specifically for cars were likely the custom fuel tanks and gearboxes developed by early manufacturers like Daimler and Panhard in the 1890s.

Why did interchangeable parts change the car industry?

Interchangeable parts made mass production possible. Before Henry Ford, every car part was hand-fitted, meaning repairs were slow and expensive. With interchangeable parts, any part from any factory could fit any car of the same model. This lowered repair costs, enabled the growth of auto parts stores, and made car ownership practical for average families. It turned cars from luxury items into everyday tools.

Are plastic parts in cars less durable than metal ones?

Not necessarily. Modern engineering plastics like polypropylene and ABS are designed to be impact-resistant, lightweight, and corrosion-proof. In fact, plastic bumpers often absorb crash energy better than metal ones, reducing damage to the frame. Metal parts are still used where strength and heat resistance matter - like engine blocks and suspension components. The choice isn’t plastic vs. metal - it’s using the right material for the job.

Can I still find parts for vintage cars from the 1950s?

Yes - and it’s easier than ever. Classic car parts are now a global industry. Companies like Classic Industries and Year One specialize in reproducing OEM parts for vehicles from the 1930s to the 1980s. Online marketplaces like eBay and forums like Hemmings connect sellers with collectors. Some parts are even 3D-printed today using original blueprints. If a part exists in any quantity, chances are someone is making or selling it.

How do electric cars change the way we think about car parts?

Electric cars eliminate dozens of traditional parts: no oil filters, no spark plugs, no exhaust systems, no transmissions with multiple gears. Instead, they rely on batteries, electric motors, and power electronics. These components last longer - a Tesla motor can run over 1 million miles - but when they fail, they’re expensive to replace. Repairs now require specialized tools and training, shifting the focus from mechanical maintenance to software diagnostics and battery health monitoring.

If you’re working on an old car, or just trying to understand why your new EV needs a software update instead of an oil change - remember: every bolt, sensor, and plastic clip has a story. The history of car parts isn’t just about machines. It’s about how people solved problems, adapted to change, and kept moving forward.

Paritosh Bhagat

October 27, 2025 AT 20:25Okay but let’s be real-plastic parts are why your car sounds like a cereal box when you close the door. I get the weight savings, but my 2003 Camry’s dash cracked in the Arizona sun and now it rattles like a toddler with maracas. We traded brass elegance for disposable engineering. And don’t even get me started on those brittle plastic clips that snap if you look at them wrong.

Sibusiso Ernest Masilela

October 28, 2025 AT 05:43You people are delusional if you think plastic is ‘better.’ It’s corporate laziness dressed up as innovation. The same companies that made cars to last 20 years now design them to fail at 80,000 miles so you’ll buy another one. And don’t pretend 3D printing is some revolutionary democratization-it’s just a fancy way to keep the OEM monopoly alive while charging $120 for a bracket you could’ve forged in your garage in 1975.

Daniel Kennedy

October 28, 2025 AT 20:00I get where you're coming from, but let’s not throw the baby out with the bathwater. Plastic isn’t perfect, but it’s saved lives. A plastic bumper doesn’t turn your fender into shrapnel in a low-speed crash. And modern polymers? They’re engineered with UV stabilizers, impact modifiers, thermal resistance-it’s not just ‘cheap plastic.’ It’s smart material science. The real villain is planned obsolescence, not the material itself.

Antonio Hunter

October 30, 2025 AT 03:43It’s fascinating how the evolution of car parts mirrors broader societal shifts. The move from hand-fitted brass components to mass-produced steel was a reflection of industrialization’s push toward efficiency. Then plastics came in as a product of postwar chemical innovation and consumer culture’s demand for affordability. Now we’re seeing the rise of software-defined parts-where a sensor isn’t just a sensor but a data node in a networked ecosystem. The car is no longer a machine; it’s a mobile computing platform with wheels. And yet, we still call them ‘parts,’ as if the language hasn’t caught up to the reality. Maybe we need a new vocabulary: ‘modules,’ ‘nodes,’ ‘integrated systems’-something that reflects how deeply embedded these components are in digital life now.

Tom Mikota

October 31, 2025 AT 20:46Uhhhh… did you know? The first ‘car part’ made specifically for automobiles wasn’t even a part-it was a patent. Karl Benz didn’t invent the engine, the tires, or the steering-he patented the integration. That’s the real origin story. Also, ‘brass radiator’? More like ‘brass death trap.’ Those things leaked like sieves and exploded if you overheated them. Thank god for aluminum. And please stop romanticizing the 1890s. No one had seat belts. People died in crashes. A lot. Like, a lot a lot.

Mark Tipton

November 2, 2025 AT 07:52Let me break this down with cold, hard data. The claim that ‘over 50% of a modern car’s weight is plastic’ is misleading. It includes foam, adhesives, undercoatings, and interior linings-none of which are structural. The actual structural plastic content? Around 12%. The rest is steel, aluminum, magnesium. Also, the ‘self-repairing’ car part narrative? Pure marketing fiction. No 3D-printed nylon bracket is going to survive 100,000 miles of vibration, thermal cycling, and road salt. And the idea that ‘anyone’ can print a fuel line bracket? Only if they have a calibrated filament printer, a CAD file with tolerances within ±0.05mm, and a certification to handle flammable materials-which most hobbyists don’t. This article reads like a TED Talk written by a PR intern.

Jessica McGirt

November 4, 2025 AT 07:21I love how this post connects the dots between engineering and human ingenuity. It’s not just about bolts and circuits-it’s about people solving problems with whatever they had. That mechanic in Oregon printing a 25-year-old bracket? That’s the spirit of the Model T era, just with a Wi-Fi connection. We’ve gone from fixing cars with wrenches to diagnosing them with apps, but the core goal is the same: keep moving forward. And that’s something we can all respect.

Jeff Napier

November 4, 2025 AT 22:47Who really decided plastic was better? Not engineers. Not mechanics. Big oil. They needed to sell more fuel, so lighter cars = less gas = less profit. So they pushed plastic to make cars lighter, then raised fuel prices to make up for it. The whole ‘fuel efficiency’ thing? A distraction. The real goal was to keep the gas industry alive while pretending to care about the planet. And now we’re stuck with plastic that melts in a fire and can’t be recycled. Brilliant.

Taylor Hayes

November 6, 2025 AT 09:29Reading this made me think of my grandpa-he used to fix his ’67 Mustang with baling wire and duct tape. He’d say, ‘If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it. But if it is, you’ve got time to figure it out.’ Now you need a $300 scanner and a subscription to a database just to reset a check engine light. I miss the days when you could learn to fix a car by watching someone else do it. Not because it was easier, but because it felt like you were part of something real.

Sanjay Mittal

November 7, 2025 AT 17:50For anyone wondering about vintage parts: there are entire communities in India that specialize in restoring pre-1980s American and European cars. We import salvaged parts from the U.S. and Europe, then reverse-engineer or 3D-print what’s missing. I’ve rebuilt a 1954 Austin Healey’s dashboard using a photo, a ruler, and a 3D printer from Bangalore. It’s not about nostalgia-it’s about preserving craftsmanship in a throwaway world.

Mike Zhong

November 9, 2025 AT 01:35If you think the car part is the object, you’re missing the point entirely. The part is a symptom. The real ‘part’ is the system of labor, capital, and ideology that produced it. The shift from brass to plastic isn’t about material-it’s about the transition from artisanal labor to algorithmic control. The mechanic who once knew the rhythm of a carburetor is now a data entry clerk for a diagnostic terminal. The car doesn’t break. The system breaks. And we’re all just replacing the parts while ignoring the machine that made the parts necessary.

Jamie Roman

November 9, 2025 AT 21:33One thing people forget: the rise of the aftermarket didn’t just make parts cheaper-it made car ownership accessible to people who couldn’t afford dealership prices. My first car was a ’98 Civic with a $20 alternator from RockAuto. That part saved me $400. And yeah, some aftermarket stuff is junk-but so are OEM parts sometimes. The key is knowing where to look. Forums, reviews, CAPA certification, asking the guy at the shop who’s been doing this since ’87. It’s not magic. It’s just knowing where to find the people who still care.

Salomi Cummingham

November 11, 2025 AT 11:10I just sat here with tears in my eyes-not because of the engineering, but because of the humanity. The mechanic in Oregon printing that bracket? That’s poetry. That’s the quiet heroism of people who refuse to let history disappear. I lost my dad last year-he was a mechanic who kept a 1964 VW Beetle running for 47 years. He had drawers full of parts no one else wanted. He called them ‘future memories.’ Now I have his drawers. And I’m printing the missing pieces. Not because I have to. But because I want to. So the story doesn’t end.

Antonio Hunter

November 13, 2025 AT 05:47That’s the thing-when you replace a thermostat or a headlight, you’re not just fixing a car. You’re continuing a conversation that started with Benz and a single-cylinder engine. That little plastic clip holding the air duct? It’s the descendant of a hand-forged brass fitting. The software that calibrates your battery? It’s the evolution of a mechanic’s feel for a carburetor. We don’t just use parts-we inherit them. And every time we choose to repair instead of replace, we’re honoring the people who made those parts possible-not just the engineers in the factory, but the guy in the garage who figured out how to make it work anyway.